Global Stories, Local Issues: Beading a Belt

April 12, 2021

For research, Scarlett Guy recreates her first ever loom piece, made in the Evening Star or Noonday Sun Cherokee basket pattern. Through beading, she attempts to understand the relationship between her cultural identity and craft practices as a Tsalagi, and how that relationship relates to broader Native American/Indigenous crafter experience.

By Scarlett Guy

The finished belt reaches 21 inches, nearly five times the length of the original loom piece.

This essay was written for the undergraduate course, "Global Stories, Local Issues," taught by Lou Brown at Duke University during Fall 2020. Students in the course were asked to research and tell stories about objects and experiences with which they had some personal connection. The course was grounded in the belief that careful attention to the details of the world around us and exploration of unexpected connections can cultivate skills and habits that help us engage more purposefully with our communities.

I am Cherokee, ᏣᎳᎩ (Tsalagi), and I practice traditional beadwork.

I began beading when I was ten years old and my grandfather drilled holes into countless dried beans to create beads for me and my siblings.

We paired the beans with corn beads to make necklaces. The corn plant, original to Southeast Asia, has historically been used by the Cherokee for crafts.[1] In my teens, I began making traditional Cherokee necklaces with tiny glass beads, the corn beads from my grandfather’s garden, and lengths of his fishing line.

I delved further into traditional beading practices in high school, when I took a traditional art class from a community elder who taught us Aniyvwiya beadwork designs and Tsalagi patterns.[2]

My first beaded piece, created using the Evening Star or Noonday Sun Cherokee basket pattern.

In class, we were asked to choose among the various Cherokee pattern templates to create our first loom projects. I chose the Evening Star or Noonday Sun Cherokee basket pattern. I liked that the diamond shapes on the side, and the star in the center reminded me of the sun and mountain ranges outlining the sky above my town.

Of all the beading styles I learned, I particularly liked looming. Unlike the beadwork styles that require beading onto a base, I enjoyed the process of creating the pattern line by line, slowly building upwards into a beadwork piece consisting only of thread and beads.

Loomed beadwork pieces are flat bands and vary greatly in length and width. This method is often used to create bracelets or cuffs, headbands, clothing adornments, and belts. My first loom piece was only about four inches long, and I remember that it took me weeks to complete it in class.

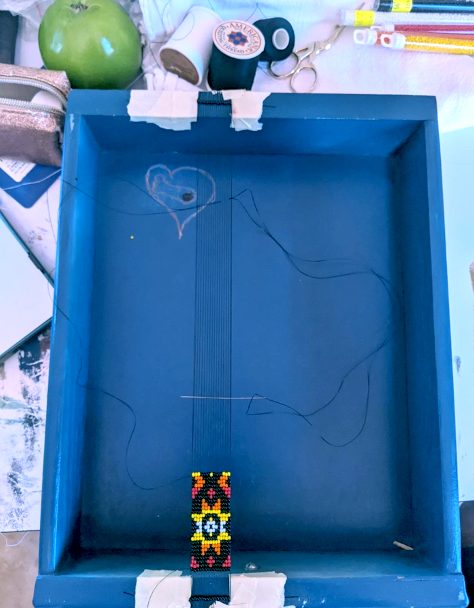

Beading supplies: black, red, orange, yellow, and white size 11 Japanese beads, black nylon thread, size 11 needle, matches, measuring tape, and thread scissors. Loom supplies: a drawer from a table given to me by my grandfather, black quilting thread, and masking tape.

Other supplies: buckskin, sinew, tacky glue, beeswax, sewing needle, pliers, dowel, and leather scissors.

"Most Native peoples did not have the time, knowledge, or resources to produce traditional crafts exactly as their ancestors had. Instead, they used more readily available materials while preserving older forms."[3]

– Public historian William S. Walker

About Native Beadwork

Native American/Indigenous beadwork is a traditional craft that has been practiced by Native Nations for centuries, both before and after European contact with Turtle Island. Beadwork is widely practiced today across Indian Country and even by non-Native individuals interested in its artistic beauty and cultural history. At times, this interest has veered away from appreciation and into cultural appropriation[4].

Little Coyote made me think about the confrontations in my life, many of which have occurred at Duke, and about how, 50 years later, I have to explain to some what Little Coyote explained to many: my buckskin is store bought.

Today, Native American/Indigenous beadwork is usually constructed with imported glass beads and nylon or cotton thread. More historically traditional materials such as buckskin, sinew, shells, clay, and stones are also used, oftentimes reflecting the cultural history and heritage of various Nations.[5]

When public historian William S. Walker speaks about the resilience of Native American/Indigenous cultural and craft practices, he speaks also to the ignorant assumptions made about Native peoples. In his journal article, "'We don't live like that anymore': Native Peoples at the Smithsonian's Festival of American Folklife, 1970-1976," Dr. Walker discusses Bertha Little Coyote, Cheyenne, and a panel discussion held on her craftmaking.

Little Coyote, a moccasin maker, mentioned to a large crowd in 1970 that she did not tan buckskin herself. As she explained, tanning had been the practice historically, and some people continued to do so, but she bought commercially tanned buckskin.

I remember my surprise on reading those words, and thinking, “duh, of course,” before realizing that non-Natives unfamiliar with Native peoples often view them as a people living in the past. This realization is something I am often confronted with in places outside of my home community.

The story of Little Coyote made me think about the confrontations in my life, many of which have occurred at Duke, and about how, 50 years later, I have to explain to some what Little Coyote explained to many: my buckskin is store bought.

"Our ancestors would use the corn beads along with commercial glass beads to sew decorations on men’s trousers or on the hems of women’s skirts. Apparently they did not use them to make belts as they do today."[6]

— Eastern Cherokee artisan Ms. Lula Nicey Welch, who learned the art of beadworking from her mother

"We make belts, necklaces, headbands, and in working with these beads, say to make a belt, we start out with a solid row of beads and then work back through until we come out with an uneven number ... And, in doing the beadwork with these large beads, we make up our own designs as we go along."[7]

— Cherokee artisan Ms. Dorothy Swimmer

Start of the loom: I am beading faster after creating the first star in the pattern. I now only glance at my pattern template.

After running out of beading thread, I seal the knot with a match before I continue.

The Individual in the Traditional

The cultural relevance of a crafter's individual aesthetics in creating their art has never been a deviation from the "traditional," but rather a celebration of individuality, which is passed down and shared.

Individuality is traditional. Our ancestors created patterns that they found pleasing, and Native artists do the same today. The relationship between a Native crafter and their art creates connection to their culture and to their ancestors, and this connection grows when traditional craft practices are taught and shared.

I have realized that I share this connection by gifting individually crafted beadwork pieces to my close friends and family. I gift beadwork when I want to show deep appreciation for someone I care about, or who has cared about me.

I will gift the finished belt to my mother, a woman with exquisite taste in hats.

The completed belt as a hatband.

Notes

[1] Pam Bakke, manager of the community youth development and adult resident services for the Cherokee Nation in 2016, discusses the Cherokee legend of the corn bead in "Crafters Learn History of Corn Beads and How to Turn Them Into Necklaces."

[2] Aniyvwiya is the Cherokee word for "principle people" and is used to refer to Native American/American Indian people.

[3] William S. Walker, "'We don't live like that anymore': Native Peoples at the Smithsonian's Festival of American Folklife, 1970-1976," The American Indian Quarterly 35, no. 4 (Fall 2011), 492.

[4] To learn more about the debate around cultural appropriation of Indigenous arts and cultures, read Lauren Goulette’s article, "How Cultural Appropriation Harms Indigenous People," and Adrienne Keene’s "New York Fashion Week Designer Steals From Northern Cheyenne/Crow Artist Bethany Yellowtail.” See also Adrienne Keene's website, Native Appropriations, for forum discussions on representations of Native peoples.

[5] Read more about the use and meanings of traditional materials and methods in the USA Today article, "Native Regalia Reflects Tribal Cultures and Histories: ‘You remember where you came from.’”

[6] Quoted in Laurence French and Jim Hornbuckle, eds, The Cherokee Perspective: Written by Eastern Cherokees (Appalachian State University Press, 1981), 178.

[7] Quoted in French et al, 179.

SCARLETT GUY is originally from Cherokee, North Carolina, and is a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. She is currently vice president of the Native American Student Alliance and secretary of the Nu chapter of Alpha Pi Omega Sorority, Inc. at Duke University, where she is studying evolutionary anthropology, linguistics, and documentary studies. She has also studied the Cherokee language at UNC-Chapel Hill, in a continuing effort to become proficient in the language.

SCARLETT GUY is originally from Cherokee, North Carolina, and is a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. She is currently vice president of the Native American Student Alliance and secretary of the Nu chapter of Alpha Pi Omega Sorority, Inc. at Duke University, where she is studying evolutionary anthropology, linguistics, and documentary studies. She has also studied the Cherokee language at UNC-Chapel Hill, in a continuing effort to become proficient in the language.

check us out

on social media