Print Culture and Resistance Among Cuban Refugees at Guantánamo Bay

July 22, 2018

Duke undergraduate Alyssa Perez talks about her experiences conducting archival research for the first time in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University. As a Cuban-America student, she is intrigued by the Caribbean Sea Migration Collection and what it reveals about the detention of Cubans and their tenacious fight for freedom.

By Alyssa Perez

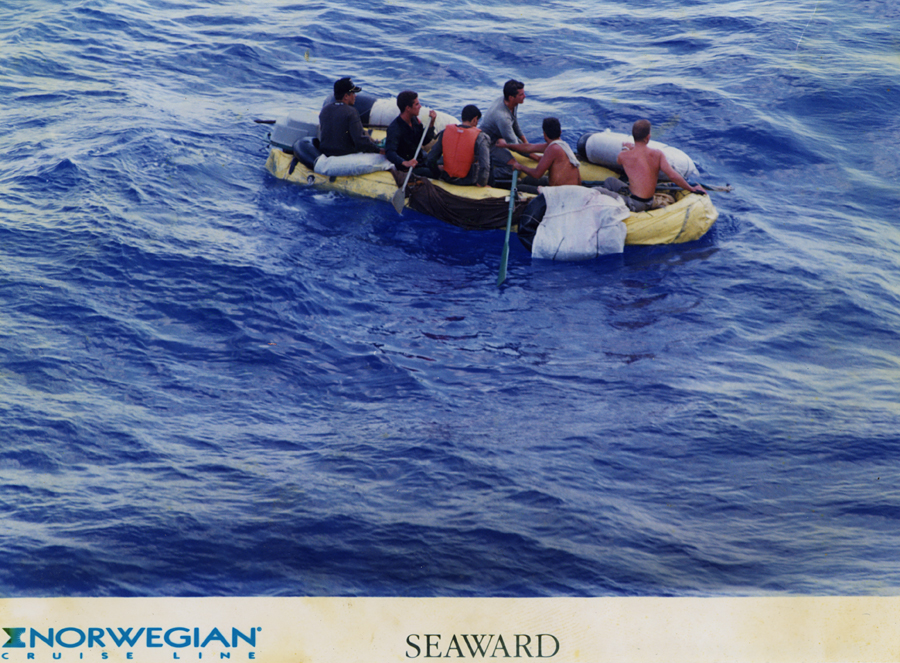

Norwegian Cruise Line, "Cuban rafters in the Florida Straits trying to reach the United States, 1990s," Between Despair and Hope: Cuban Rafters at the U.S. Naval Base Guantánamo Bay, 1994-1996, accessed June 3, 2018.

As a descendant of Cuban migrants and a Miami native, I am no stranger to migration stories.

I spent hours of my childhood questioning my grandmother about her story. Each story builds a narrative, and what I discovered in the archives helped me contextualize the countless stories that have defined all of Cuban migration. The long history of U.S.-Cuban relations encompasses the equally long history of Cuban migration. The United States saw four distinct waves of Cuban migration: the initial 1959 wave, the Camarioca boatlift of 1965, the 1980 Mariel boatlift, and finally the mass exodus of Cuban rafters in 1994. The conflicts resulting from each wave were complex, unique, and fascinating. The stories of the refugees are similarly captivating.

Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library houses the Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, 1959-2014. Its materials, which include photographs, newspapers, and artwork, provide valuable glimpses into migration stories and contain remarkable representations of Cuban culture, creativity, and ingenuity.

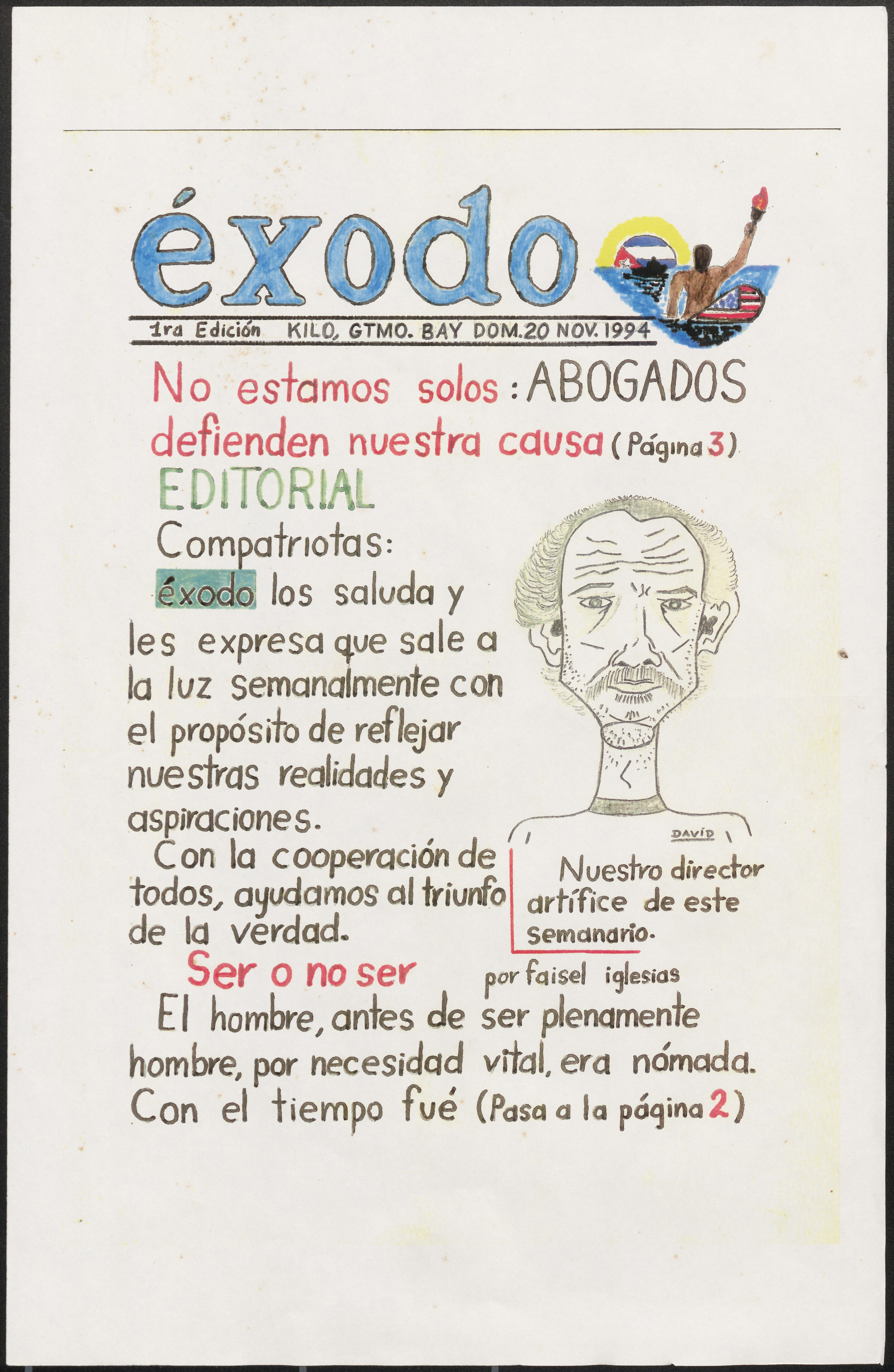

As I opened my first box of the Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, I stumbled upon an issue of éxodo. The quality of the art initially caught my eye and I fell in love with these papers and the stories that they told. The prints are larger than the average newspaper and incorporate an array of colors within the blocks of text. I learned later that éxodo was created in response to the military-produced newspaper ¿Que Pasa?, which circulated throughout the Cuban camps at Guantánamo Bay. ¿Que Pasa? was produced by the MIST, or Military Information Support Team, that created newspapers for rumor control and information sharing. MIST created a similar newspaper in the Haitian camps at Guantánamo called Sa K’pase. éxodo is a look into the Guantánamo Bay camp Camp Kilo, and the weekly editions posted in the camp center now reveal the evolution of life at the camp.

éxodo captured the creativity of the detainees and embodied their intelligence. Detained refugees broke with stereotypes of Cubans as uneducated, vulnerable, and complacent by formally organizing their community. Their ability to create print media in light of the poor initial living conditions reflects their deeply rooted and unifying desires for liberty and freedom.

éxodo offered an array of content, including articles, comics, and weekly horoscopes. While horoscopes are generally simple and often arbitrary, they showcase different aspects of human life and nature, such as stress, fear, and anxiety. The content of horoscopes can be creative and ingenious, and their inclusion in the pages of éxodo marks them as an important element of Cuban rafter culture. Some horoscopes advised readers to "change cigarettes" and "stop renting magazines." Others suggested that they "think mostly about their families in Cuba" and "bathe every day." One from December 18, 1994, read: "Ask what you want from Santa Claus. He is coming to Guantánamo with everything except visas, because he left them in Havana."

"Your lucky number is 8." éxodo, 2nd edition, 1994 November 27, éxodo, Issues 1-6, Box 1, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. éxodo, 2nd edition, 1994 November 27, éxodo, Issues 1-6, Box 1, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

"Your lucky number is 8." éxodo, 2nd edition, 1994 November 27, éxodo, Issues 1-6, Box 1, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. éxodo, 2nd edition, 1994 November 27, éxodo, Issues 1-6, Box 1, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

The horoscopes, while modest and at times ridiculous, created and enforced narratives about the guidance and hope that detainees wanted to hear. The horoscopes in the pages of éxodo used simple language and offered advice on how to better life in the camp. They acted as a way of self-policing the community. Cuban detainees were at the mercy of the guards within the military-controlled camps. Guards policed detainees and encouraged peaceful existence to encourage parole. The newspapers were both a form of self-expression and a way to guide the community into correct behavior. The refugees could read their horoscopes and learn lessons and "rules" from their own people. Horoscopes became one way of showing how freedom and recognition could be earned through what was considered at the time to be good, respectable behavior. Cuban culture still today embodies community and unity. The horoscopes in éxodo maintained that sense of community while hinting towards the daily struggles of the detainees.

The page of horoscopes in a later edition of éxodo. éxodo, 20th edition, 1995 June 18, éxodo, Issues 19-25, Box 1, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

The Caribbean Sea Migration Collection houses other newspapers that circulated in Guantánamo Bay. They offer insights into the cultures of specific camps and raise questions about camp relations and inequalities. The Collection shows how individual experiences translated into amazing works of art, which themselves shed light on the struggles, creativity, and hope among detainees in the camps.

éxodo and the other Cuban newspapers from Guantánamo inspired me to learn more about the conditions of the camps, inter-camp relations as well as refugee-U.S. military relations, and how refugees organized in response to the conditions. Detainees had far more freedom of expression than I could have ever predicted. I am intrigued by the art produced at Guantánamo and its reflection of what it meant to be a detained Cuban refugee. The Collection leaves me questioning how culture is revealed through art, and the determination of the Cuban detainee community to continue to create, even under immense oppression.

Cuban camp, Guantánamo, 1994, Cuban camp, Guantánamo, Photographs, 1994-1995, Box 3, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

An art gallery established by refugees in the camps of Guantánamo Bay showcased art created by Cuban detainees. Artwork in tent, Guantánamo, Photographs, 1994-1995, Box 3, Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

The 2018 Story + team Remapping the Caribbean: Archives of Haitian & Cuban Migration, Detention & Legal Activism partnered with the John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute @ Duke University to explore the archival collection of the National Coalition for Haitian Rights. The group consisted of Professor Laurent Dubois, Duke History PhD student Ayanna Legros, and three undergraduates: Aasha Henderson, Sanha Lim, and Alyssa Perez. Through an analysis of photography, archival documents, first-person testimonies, and organization documents, we sought to understand the genealogy of immigration to the United States in the context of Cuban migration from the 1970s to the 2000s. We focused on human rights abuses of Haitians within the island and in the diaspora to understand the particular challenges Haitians have faced while crossing borders to escape political, economic, and social unrest in Haiti. As part of the Story+ project, the team created a Wikipedia entry, wrote blog posts, and conducted interviews with original board members of the organizations, with the goal of elevating the experiences of Caribbean peoples by showcasing how important first-person accounts and testimonies are in battles for human rights.

ALYSSA PEREZ is a rising junior in Trinity College of Arts and Sciences at Duke University, where she is majoring in History and minoring in Global Health. Alyssa was born in Miami, Florida, and as the granddaughter of Cuban refugees has always been fascinated by their culture in the context of migration history. She was a part of the 2018 Story+ team at Duke.

check us out

on social media