The Possibility of a Public

April 7, 2017

On March 3, 2017, the Forum for Scholars and Publics hosted a conversation between Corey Robin and Jed Purdy about the purpose and promise of public intellectuals in the United States today. Scholar/activist Peter Pihos reflects on the discussion and its intersection with his own recent experiences.

By Peter Constantine Pihos

Jed Purdy and Corey Robin in discussion at the Forum for Scholars and Publics.

A month before the first primary voters cast their ballots in 2016, The Chronicle of Higher Education published an essay by Corey Robin, Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College, entitled “How Intellectuals Create a Public.”

The essay argues that to be properly public, an intellectual must write for an audience that does not yet exist, but might become. This requires both the author’s belief in and the audience’s capacity for collective transformation. After decades of reduction, degradation, and privatization of anything labeled public, the presidency of Donald J. Trump might seem to mark the nadir of possibility. Yet, despite this wicked portent, Robin’s recent conversation at the Forum for Scholars and Publics with Jedediah Purdy, Robinson O. Everett Professor of Law at Duke, evinced a curiously resurgent optimism.

The Limits of Politics and the Waning of the Public

In the despair and confusion of those November days, I read what seemed like hundreds of Facebook posts all essentially asking the same question: "What should I do?"

The reaction of many of my friends and colleagues to the recent election demonstrated just how limited our conceptions of politics, and with it our notions of the public, have become. In the despair and confusion of those November days, I read what seemed like hundreds of Facebook posts all essentially asking the same question: “What should I do?” Their sincere concern manifested the very problem it sought to address. Beyond giving money, few of my largely liberal, professional, middle-class Facebook friends were connected to any institutions involved in what I consider to be the actual activity of politics, that is, collective action to build socially-meaningful power. A second version of the post-election question (coming from friends in Brooklyn, or Oakland, or Chicago) drove this home: “Since I live in a blue state, what can I do?” This implied that because these places vote overwhelmingly Democratic in presidential elections, the real political work lies elsewhere. This narrow view of politics as a mere domain, which animates wide swaths of liberal thought, is what Robin critiques from the Left.

In recent months, the Facebook hive mind has suggested actions, which many of us have undertaken. Subscribe to the New York Times and the Washington Post. Donate to the ACLU and Planned Parenthood. Call your Congressperson and attend their town halls. Some are quite useful but remain highly individualistic. People are not inert, but they are atomized. This is precisely the result of the great winnowing of our conceptions of power and politics that has taken place in the last forty years of U.S. history. Over that period, the historian Daniel T. Rodgers describes in The Age of Fracture, “One heard less about society, history and power, and more about individuals, contingency and choice.” Telling us that we no longer needed to be bothered with the activity of politics when we had efficient markets, politicians (and the big money that bankrolls them) have for decades sought to relieve us of even the aspiration to become a public.

Intervening at this historical conjuncture, Robin’s essay takes what at first blush appears to be a normative inquiry—what should a public intellectual do?—and turns into an analysis of the definition of public in the phrase public intellectual. In his imagination, the “public intellectual is a political actor” who “wants her writing to have an effect, to have all the power of power itself.” This power exists in the relationship between the intellectual and her public. Rather than writing to an audience that exists, “the public intellectual is always speaking to an audience that is not there.” Robin argues that, like Prospero, she must summon it into being, to create by writing the public for which she writes.

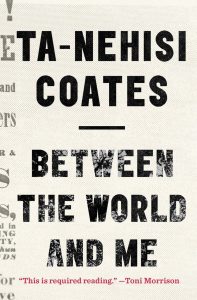

Much of the substance of Robin’s case is made through critique, by showing why the writings of two widely-read liberal intellectuals, Cass Sunstein and Ta-Nehesi Coates, are insufficiently public. Both provide “an all too accurate reflection of the world we live in,” one that fundamentally disavows the political transformation. “The presupposition of their writing is that a politics unafraid to put division and conflict, the mobilization of a mass, on the table, is in fact off the table.” They do so in very different ways. Sunstein’s “nudge” libertarianism disavows collective life in favor of channeling individuals towards good choices, as they already imagine them. By contrast, what Robin describes as Coates’s “apocalypticism” leads him to fear the very power that would be necessary to redress the conditions he chronicles. As Robin puts it, for Coates, “the condition of black Americans must be overcome but there are no political means to overcome it.” Coates desires a new public, but he does not believe in it.

Much of the substance of Robin’s case is made through critique, by showing why the writings of two widely-read liberal intellectuals, Cass Sunstein and Ta-Nehesi Coates, are insufficiently public. Both provide “an all too accurate reflection of the world we live in,” one that fundamentally disavows the political transformation. “The presupposition of their writing is that a politics unafraid to put division and conflict, the mobilization of a mass, on the table, is in fact off the table.” They do so in very different ways. Sunstein’s “nudge” libertarianism disavows collective life in favor of channeling individuals towards good choices, as they already imagine them. By contrast, what Robin describes as Coates’s “apocalypticism” leads him to fear the very power that would be necessary to redress the conditions he chronicles. As Robin puts it, for Coates, “the condition of black Americans must be overcome but there are no political means to overcome it.” Coates desires a new public, but he does not believe in it.

Can we find new intellectuals? Corey Robin and Jed Purdy, perhaps? Robin recognizes in the final few paragraphs of his Chronicle piece, that there are Left intellectuals writing in a properly public vein. But there remains an arresting problem that goes beyond the political visions of intellectuals themselves: the limited political horizon of their audience. If people no longer engage in the activity of politics, the possibility of an intellectual creating a public attenuates. Robin does not name any contemporary public intellectuals as lodestones to follow, and not because of individual authors’ failures. Rather, the possibility of public life itself may have evanesced. It’s not “that there are no intellectuals but … that there seems to be no possibility of a public.”

Can we find new intellectuals? Corey Robin and Jed Purdy, perhaps? Robin recognizes in the final few paragraphs of his Chronicle piece, that there are Left intellectuals writing in a properly public vein. But there remains an arresting problem that goes beyond the political visions of intellectuals themselves: the limited political horizon of their audience. If people no longer engage in the activity of politics, the possibility of an intellectual creating a public attenuates. Robin does not name any contemporary public intellectuals as lodestones to follow, and not because of individual authors’ failures. Rather, the possibility of public life itself may have evanesced. It’s not “that there are no intellectuals but … that there seems to be no possibility of a public.”

Political Optimism in the Age of Trump

In reading Corey Robin’s essay after his conversation with Jed Purdy at the Forum for Scholars and Publics, this final line quoted above jumped out. Despite the intervening year in which American voters elected Donald Trump President, Robin and Purdy evinced certain optimism. Their conversation highlighted how the terrain for intellectuals has changed, a reality evidenced by where their bylines have appeared since each of them began writing in magazines and on the internet at the turn of the 21st century. The presence of new outlets, like n+1, and Jacobin, has created a space for writing Left politics. While these outlets remain niche, they evidence the growth of a broader ecosystem. Indeed, Robin professed to having learned much from the generation of graduate students and young academics who write in these magazines, who have come of age in a moment of constricting possibilities within the university and been seemingly emboldened by it.

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 13, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

These magazines and writers existed prior to 2016. What changed was their relationship to American electoral politics. Only slightly less likely than Trump winning the Presidency was the possibility that a self-declared Democratic Socialist from Vermont would receive more than forty-three percent of Democratic primary votes, of more than thirty million votes cast. The optimism resulting from Sanders’ relative success is not just a matter of the particulars of his policy positions or his campaign’s innovations in “distributed organizing.” In this context, what was most salient about Sanders’ politics was the understanding of politics and power that he offered, a vision quite unlike that of any challenger from the left of the Democratic establishment in decades. Sanders argued for democratizing the economy and politics against the corrosive influence of what Louis Brandeis once called “the financial oligarchy.” To do so would require staking out a much broader domain for political life than the narrow slice recognized by mainstream liberals. Indeed, it may be that the legacy of the Democratic primary battle is this reexamination of the boundaries of political life, both in terms of what we subject to political decision-making and how we create our political solidarities. Without being too glib, we might say that the campaign was waged in favor of the possibility of a public, one that does not yet exist.

But Sanders lost, and so did Clinton. Unsurprisingly, we—the audience at the Forum for Scholars and Publics—were interested in Purdy and Robin’s ideas about the intellectual’s place in light of Trump’s victory. It was a remarkable setback for hopes of more social democratic policy, and his politics and policy are a danger to members of our communities and to the health and survival of our polity. Nonetheless, the discussion circled back multiple times to the opening Clinton’s loss created for the Left to contest power within the Democratic Party. As Corey Robin argued, the Clinton campaign lost the race; too many Obama voters staying home because of Clinton campaign strategists’ decisions to rely on demographic microtargeting over in-person contacts, and their choice to place more emphasis on her opponent’s personality rather than on the fact that his policies would serve an economic elite while harming poor and middle-class Americans. The question for the Left is whether it can simultaneously oppose Trump and protect the most vulnerable while also defeating Clinton-style politics.

PHOTO © AL BURGESS

Answering this question is a self-evidently political task, and both Purdy and Robin seemed to agree that Left intellectuals must convince liberals to choose a different approach. Many in the audience wondered why this focus on liberals, rather than the Trump voters who are the object of so much (maudlin) concern in the media. The speakers’ answers did not dismiss as unimportant Trump’s voters or the many who did not vote. Rather, they highlighted the opportunity to transform politics into an ongoing project of building power, a power that can be used to expand our collective control over the institutions and practices that structure our lives, whether in heavily “blue” states or “red” states. This activity must take place inside the apparatus of electoral politics—such as contesting for power within the Democratic Party where it is permeable—but, even more importantly, by creating and building upon solidarities elsewhere. Fundamentally, such solidarities take trust, which makes intellectuals at Duke and Brooklyn College perhaps unsuited for the task of convincing too many people in rural Michigan that a different sort of politics is possible. What we can do is to articulate a politics within which the many people who find themselves left out of a winner-take-all economy can recognize their shared interests.

What we can do is articulate a politics within which the many people who find themselves left out of a winner-take-all economy can recognize their shared interests.

I do not take lightly Republicans’ capacity to do harm, nor can a serious social democratic politics welcome any aspect of the pain that it will cause for people who can little afford it—even those who voted for Trump. But I cannot help but hold out hope that Republicans’ actions may still operate as a catalyst. We have seen the anger and the eloquent testimony of a wide variety of people about the potential repeal of the Affordable Care Act. Even more important, as Jed Purdy highlighted, was our reaction to the administration’s Muslim Ban, which saw semi-spontaneous protests at airports all across the country. We did politics where it is not supposed to happen, confronting the operations of the national security state at one of its most opaque and well-secured locations. This “we” included people who are often thought of as being outside of our political imaginary, including the most demonized: non-citizens and undocumented migrants. While the airport protests reflected solidarity with people at the margins, they also were more than that, as our politics must be if we hope to create a coalition strong enough to take power. Few would have imagined these protests even a week, or two days, prior. But in those moments, however fleetingly, we brought a public into being.

Banner image: By David Geitgey Sierralupe from Eugene, Oregon (Rally Against the Immigration Ban) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

PETER CONSTANTINE PIHOS is a Lecturing Fellow in the Thompson Writing Program at Duke University and a member of the Duke Faculty Union. He is working on a book about black police officers and the transformation of criminal justice since 1965, called Black Power Through Law. He has been a visIting faculty member at Deep Springs College and the seminar co-leader at the Arete Project. He tweets as @PeterCPihos.

PETER CONSTANTINE PIHOS is a Lecturing Fellow in the Thompson Writing Program at Duke University and a member of the Duke Faculty Union. He is working on a book about black police officers and the transformation of criminal justice since 1965, called Black Power Through Law. He has been a visIting faculty member at Deep Springs College and the seminar co-leader at the Arete Project. He tweets as @PeterCPihos.

check us out

on social media