PRACTICE: Listening to Nathaniel Mackey and Abdullah Ibrahim

November 24, 2015

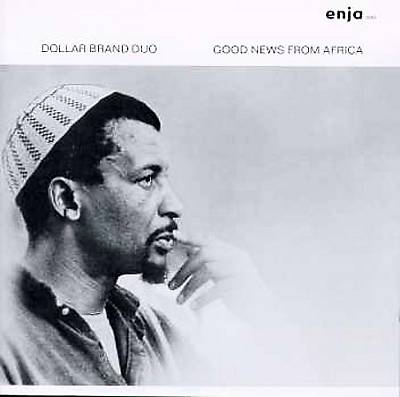

A few weeks ago I started writing a series of commentaries on contemporary African poetry for the online poetry journal, Jacket2. I am always terrified of the blank page, and so I scrolled through my iPod for some sonic courage. When Abdullah Ibrahim’s 1974 album, Good News from Africa, appeared I knew I’d found what I needed.

By Tsitsi Jaji

Nathaniel Mackey and Abdullah Ibrahim at the Forum for Scholars and Publics.

The album opens with “Ntsikana’s Bell,” a song attributed to a Xhosa religious visionary who lived in the seventeenth century, and the other tracks draw on traditional Swazi and Cape Muslim music. The album’s revelatory improvisations are anchored in indigenous and diverse traditions. That aesthetic resonates with a phrase Ibrahim kept returning to in his conversation with Nathaniel Mackey: ancient traditions, new relevance, or new technology. The two men are, needless to say, towering giants of their respective art forms and perhaps the most important point of convergence is their deep exploration of breath.

One of Mackey’s daily practices is to post a clip of music on Facebook by a musician whose birthday he celebrates, and so he opened the conversation by inviting the audience to join in celebration of Ibrahim's 81st birthday, which had just passed the previous week. Ibrahim’s tall stature is unbowed by age. But the pacing of his speech and the way he refers to himself with what Southern African languages use as the plural of respect reveal him to be an elder completely at ease taking the time to reflect, listen to silence, and craft answers that say more than was asked. The deep vitality of Ibrahim’s music is anchored in the intertwining practices of music -- “We used to practice 24-7, now it’s 25-8” – and bu-do -- a Japanese art of “no-fighting.” Bu-do is rooted in movement, the mastery of breath and the breaking down of ego, and it is an art form he has been studying for 5 decades. Bu-do’s integral principle is the continuous repetition of basics.

In his concert Friday night, several of the songs Ekaya performed with him are ones that he has been playing for decades. There was a magnetic continuity linking the homophonic choral passages when the wind instruments played in perfect unaccompanied sync with a series of dazzling solos in which we witnessed the musicians’ discovery of never-before-heard breath. In their performances, what Ibrahim had said in the conversation about being “the first cyber-space people,” who were uploading soundbytes through hours of practice that could then be accessed at breakneck speed made sense.

Like Ibrahim’s music, Mackey’s poetry has included a continuous return to a single form for the last thirty years, The Song of the Andoumboulou, a series of poems now numbering 160. Mackey’s first collection, Eroding Witness, introduces the series, and “Song of the Andoumboulou: 7” bears the epigram “—ntsikana’s bell—”. Like an unknown prophecy, the poem convinces me that Mackey’s conversation with Ibrahim has been long in the making, the universe’s answer to a hanging phrase of music, poetry, breath. In the song, Mackey writes:

This I

heard my own self say,

the

new day,

begins…

and the poem continues:

Possessed, I

stroke the baobab’s rooty wood,

whose various branchings

echo this, our

remembered song.

In a similarity some of Ibrahim’s first listeners recognized between Thelonious Monk’s music and Ibrahim’s, Mackey could hear another principle that structures his playing and philosophy: the relationship between breath and memory. For Ibrahim, this connection is illustrated in our first and last moments of existence – the newborn’s inhalation before the first cry, as automatic as the last breath. And yet, for Ibrahim, what makes humans unique is our ability to control and change the rhythm of our breath. At one point in the conversation, Ibrahim talked about how the center of energy in bu-do is in the lower abdomen – this is a deep and bodily grounded breath. Another musician-mentor of mine, Jacques Coursil, used to say that one plays the piano with one’s haunches, and that grounded gravity has always been an important part of my own music-making. I think it’s what lets the rhythm section hold down the beat in an improvisation, no less than what anchors the 2 against 3 meters in a Brahms intermezzo, or the tabla patterns in classical Indian music.

Ibrahim’s musical vision reaches beyond the world of sound. His devotion to the convergence of ancient tradition and new relevance reminds us that in traditional societies, music and healing operate on the same principle, and that when one is “given the talent of dealing with music it has nothing to do with entertainment. It is a way, a method we’ve been given to delve into what is regarded as unreality and how we can impart that.” For nearly a decade, he has been developing a project named M7, which aims to impart this ancient information to young people. Recently he purchased a farm in the Northern Cape, located in the desert whose formless form challenges the Cartesian lines of design and thought of Western perspectives. There he’s building a center where young people may study music, memory, medicine, meditation, movement, menu, and martial arts as inter-woven practices. The project, like so many of his compositions, is about people and place. Ekaya, the name of his ensemble, means “at home” and M7 is making a home for the “trance-mission” of the complexity of traditional and improvisational arts. And listening to his ensemble play in the structures of Ibrahim’s compositions in his recent visit to Duke was like being invited into the house of his imagination, where everything moves in Dream Time.

Having been lucky enough to witness the concert and conversation, the performance drew me back to the world of music. It was as moving to watch Ibrahim listening from the piano and dancing with the subtle shifts of head and torso in response to his septet’s playing as it was to hear the large sound of his own piano work interjecting from time to time. I was reminded that whether surrounded by sound, or playing it, music allows us to enter a different mode of time, a different mode of inhabiting the world. I went home, and sat down at the piano. After too much time away, I am ready to practice.

TSITSI JAJI is Associate Research Professor in the Department of English at Duke University, where she teaches courses on African American, African and Caribbean expressive cultures and exchanges among them throughout the global black world. Her research often focuses on representations of sound, music and listening, and engages feminist methods and theory. She also holds a B. Music in piano performance from Oberlin Conservatory, and still finds making music an important part of her life on and off campus.

TSITSI JAJI is Associate Research Professor in the Department of English at Duke University, where she teaches courses on African American, African and Caribbean expressive cultures and exchanges among them throughout the global black world. Her research often focuses on representations of sound, music and listening, and engages feminist methods and theory. She also holds a B. Music in piano performance from Oberlin Conservatory, and still finds making music an important part of her life on and off campus.

check us out

on social media